Land Survey 101 Transcription

Well good morning everyone my name is Keith Hulen. I’m the director of business development here at Ascent Geomatics Solutions. I’m joined today by our honorable and esteemed Mr. Michael Pool. Michael, you want to tell us a bit about your background.

I’m a civil engineer and a land surveyor. I graduated from California Polytechnic San Luis Obispo with a bachelor’s in civil engineering and I am the engineering manager here at Ascent Geomatics.

Excellent. So, you know a little bit about land surveying then.

That’s the claim, yeah.

Alright so that is the topic today. This is a recorded webinar. I wanted to let everybody know that if you have any questions please feel free to just go to the orange arrow up in the top right-hand corner. You hit that button and then you should see an area there for questions and you can submit those. We’ll answer any of the questions at the end of the session. Today’s topic is going to be land surveying 101, and we’ll get our slides to advance here. Here we go. What the idea behind this today is, there’s a lot of folks that are just coming new into their industry maybe it might be oil and gas it could be in the civil infrastructure or transportation space. We wanted to do this for many different reasons. One was just to give some of those folks a good idea about what land surveying is. And then another is to really kind of teach even folks that have been working with land surveying maybe sub out some of these services to understand a little more about the background and why land surveying isn’t not easy, and some people may claim it to be. Because it certainly is not so with that let’s go ahead and jump right in.

Michael maybe you could explain to me.

Let’s start very basic here and just explain what is land surveying?

Land surveying in a nutshell is the locating features spatially on the earth’s surface. That’s the simple terms, just where is something.

Where it is in relation to something else? Is that looking at vertically, horizontally? How is that a factor?

Yeah. Where is it located on the Earth’s surface and we try and do that in many ways either from a location that we might call a control point or with GPS technology today we use latitude longitude. We’ve got the equator of the earth and the prime meridian up there in England.

I’ve been on plane. I’m sure you’ve been on a few planes in your day and as you’re huge grid system. Tell me a little bit about that and why that is such a perfect kind of a grid system.

Well it’s certainly not perfect but that was the aim many, many years ago. But yeah, you’re flying over that. You know even when I was flying as a kid what are all the squares. Why does it look like a big checkerboard down there? And Thomas Jefferson way back in 1700’s he knew that you know we were going to be expanding and everything and then he had a forethought to that hey we need some kind of system of laying out this land and subdividing it. So that was sort of the birth of that. And we came up with the public land surveying system in the 1800’s.

Great. And I think we’re going to talk about that in a little more depth here. This isn’t by accident that this looks this way for a reason. Yes. All right so how did we get here. You know looking at obviously there’s a long history that kind of goes along with land surveying. Right. This isn’t some new concept. Sure, we use new tools today, but this is not a new concept. Even Thomas Jefferson when he laid out this system, which we’ll talk about in a minute, it wasn’t even new to Thomas Jefferson right. This is something that’s been going on for a very long time.

Thomas Jefferson was a surveyor himself before he was president surveying goes back all the way to the Egyptians the pyramids didn’t just happen. They had some smart people and some sophisticated tools and that’s how the pyramids got built.

Well pretty much anything right. I mean if you look at the bottom right hand picture that the seven ancient wonders of the world you don’t build structures like that thousands of years ago. Unless you’ve got some way to build it. I mean you know you look at the pyramids there’s two and a half million blocks in that there’s no way that you’re going to put two and a half million blocks at twenty tons. And if it’s not by inches or a foot that’s going to make a really big difference. On the other side of the pyramid so they had to have some sort of a way to do that right.

Absolutely.

So how did they do it? No, I’m just kidding.

I know that’s a big mystery.

Yeah, this is a surveying seminar.

Yeah, they just I think maybe they use water. I’ve heard that’s the technique that they used, and a lot of different types of methods, but either way throughout time it’s been used. And then here in the U.S. in America obviously we know George Washington was a surveyor. Thomas Jefferson was. And then I guess help me out with this. But was it not right after the Louisiana Purchase that we started to kind of as we were moving and expanding west when we started to put in this system of the PLSS system to break up these different areas.

Yeah. The original 13 colonies those were all done by what’s called meets and bounds, it’s just like you know go along a fence, you get to a tree and you follow this line of rocks until you get to this other tree. And that just wasn’t as simple. They wanted something that was going to be a little more distinct and easily and easier to follow.

And those are still in place in a lot of different states, meets and bounds, I know in Texas they still use that.

Texas is a little bit different. They’ve had four or five different countries that have owned that land in France and then the Spaniards and then Mexico and then the Republic of Texas and now finally the United States. Lots of different ways they doled out land down there so there was some meets and bounds. There was some very similar to ours. Sectionalized lands. But yeah Texas is different. And then there’s the 13 colonies that are still meets and bounds and then the remainder of the United States except for small portions of California and a few others. But it’s all PLSS public land survey system.

Okay well let’s talk about this. PLSS that we keep mentioning, the public land survey system. For a layman like me in layman’s terms how would you explain with the PLSS is?

It’s a way to subdivide the land and it’s broken down into sections 640 acres which turns out to be a mile by a mile. And then those are in townships of 36 sections six by six and then you have meridians all over the United States. That principal meridians that those are all laid out by. So we here in Colorado were mostly in the sixth principal Meridian other places North Dakota are in the fifth, and Montana has its own principal meridian in Montana and New Mexico has its own.

Well I’m an expert on meridians of course but for anybody that might be listening maybe you just explain what you mean by a meridian.

Meridian is an arbitrary line that goes through the point that somebody, I don’t know if they threw a dart board or what, but they chose something obviously a little bit more specific than that. But it’s a base line that we talk about meridians north of a certain line or south of a certain line and east or west of a certain line. So those are the base lines in the meridians the base line runs east. It’s a line that runs east west and we measure north and south of it and the meridian is north south running line that we measure east and west of.

All right. Again, just kind of recapping that PLSS here is that you’ve got a township right and the township will house 36 sections, is that correct?

That’s correct.

All right. And then the section is going to be 640 acres that correct?

Ideally. Yes.

And then ultimately that section can be broken down a little bit further. Right. We can look at. Here’s an example of a section there that you can see the 36 sections down in that graphic in the middle. And then to the top right you can see that section broken down. Then you start to get into a quarter, and a quarter-quarter, and it just continues to break down. Right?

Yes. That was the whole idea behind it if somebody wants an entire section of land or they just want a quarter of a section maybe they buy a quarter and then they have three kids and then you know in their will, they dole that out by quarter-quarters and just keep subdividing from there.

And as you can see there are a couple of the bullet points we talked about this you know being done back in the late 1700’s and they did one and a half billion acres. I would have loved to get that contract breaking down one and a half billion acres, that would’ve been nice, huh?

Yeah. You start tomorrow.

Yeah. Great. Well let’s talk a little bit more about this township, section, also range right. You hear that a lot. The township section range. So how does range factor into this?

Range, well there you can see the principal meridian the baseline that I was talking about. We call those townships, those 36 sections. As we measure away from the baseline the meridian will say, township 9 north range 68 west so that’s 9 lines north of baseline and 68 away from the meridian so that’s, not sure where the range came from but that’s the township and range. And then we’ll narrow it down to a specific section within that township here you see township 2 south range 3 west and Section 14.

Right, ok. And this really narrows down the area. And then each one of the corners is going to have some sort of a monument in place, and we’ll talk about monuments here in a minute. Right?

Yes. They went out and supposedly I mean this was back in the 1800’s, 1860s 50s and such. But they put stones or charge stakes, things like that.

And so, where we see the PLSS in place today obviously a good portion of the U.S. is mapped in this way. And as you mentioned earlier the 13 original colonies and then Texas is kind of its own animal, there’s a lot of different methods a lot of different systems used over the years. But most of the U.S. is using this type of a system.

Yep, everything you see in blue. Like I said except for a few areas in California and the some of the reservations is all PLSS.

Okay that makes sense. So again, if we’re talking about history here obviously they weren’t using GPS and drones I imagine back in the early 1800s right as they were going out surveying so.

They wish they were.

So, these are some of the tools you probably used early in your career maybe to tell us about some of these.

I’m not that old.

So, what you see on the right there in the street is it’s an old Gunter’s chain and that’s how the original sections were laid out. There is a hundred of these little links on there and that made 66 feet for one chain and then 6.6 feet for a link. And how those were all laid out using those chains and then just some guy making sure you stayed online. Pretty cool stuff. And then old transit there in the middle that’s how you know in the ancient days we turned angles and there might even be a little star guide there on the top too. You can take measurements off Polaris and then an old compass on the left.

It’s incredible if you think about it. The fact that they were able to get to put in place this grid system as good as they did with these types of tools. I mean you think about what we use today and GPS, things like that were amazing that they were able to do that with these types of tools that are, in a way primitive, with how we look at them today.

Absolutely. And it’s amazing the accurate how well they did out there.

And they’re sleeping out there in tents, right. I mean they’re going across this land and sleeping out there with the elements and the animals and all that.

And the Indians.

Sure, the Native Americans would have certainly been a challenge. Yeah that would’ve made surveying a little bit tougher. Back in the day.

So, let’s switch gears a little bit. We talked about the history of what is land surveying. Where did it come from? But now let’s switch gears and kind of talk about who needs or who uses land surveying today. Why would you have to have land surveying?

Got to locate things and figure out where they are on the Earth’s surface. I mean that’s the whole basis of land survey it’s finding these things spatially and where am I? You are here. You’re that red dot on the map.

So, you’re going to use this for if you’re going to put in place a new building. You’re going to put in place a new house. You’re going to put in place a new oil and gas pad, you’re going to put in place a new highway. Same thing is that a fair statement to say that anything that is going to be built would need to have some sort of land surveying included?

Anything that’s going to be built, any large purchases large real estate purchases or refinance or something like that the lender might require a survey. Like I said, it’s all spatial. Where is the thing that I’m going to finance or where is the thing that you want to buy? Not being built. But you know they want to know where it is and relative other stuff around it to make sure that you know the neighbor next door is not going to have claim to this property that I’m helping you buy.

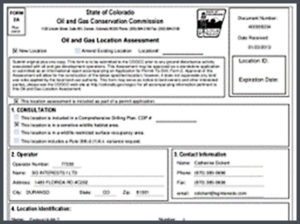

Yeah, I think we’re going to talk about that in a minute or two. You know what some of those repercussions could be. But essentially anybody that’s getting new property building on that property anything like that must be some sort of land surveying, because we need to ensure that that is accurate where we’re going to lay that building, put that house put that oil and gas pad, things like that. Right. And too is an example you know every one of these would be an example of you know part of an exhibit package that would get put in place where the surveying has been done. Tell me a little bit about you know what this depicts here.

On the right side is a well-location certificate. So, we’re going out and we’re telling the operators you’re where you want to put a hole in the ground and get some black sludge out. And relative to that section this is where it is, and this is what is required by the Colorado Oil and Gas Commission and then on the left side is a grading plan you know the surveyor went out there and said here’s the topography of the ground and here’s how you’re going to grade this so that they put a rig on there that’s something flat so that the rig doesn’t fall over.

So, on the right obviously there is regulation that the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission put in place saying that you must be a certain distance from a building or other type of units, but a building unit being a very important one someone’s house. So, this would ensure that they are within those regulations on the right side right. Making sure that they are abiding by all the rules and regulations of the COGCC.

From a very macro point of view. Yes.

And then on the left side is you know gathering that topography you obviously want to lay these pads as flat as you can get. That’s the grading plan and the cut-fill as you hear those terms, meaning this is how much ground we need to cut out, this how much ground we need to fill in, to make that a flat surface right. That’s very important especially in a place like Colorado where there’s quite a bit of different undulations in there, it goes all the way up to 14000 plus and obviously down to 5000.

Around three or four thousand is good you get.

Okay. So, there’s a huge variation there. So that’s important. So, you know when we talk about when is land surveying needed you know we talked about kind of who would use these services. Anybody going to be kind of building this, but when is it needed? So, you can see this list. Planning, designing, construction, as-built, and demolition. Maybe you could just quickly touch on each one of these very quickly how land surveying you know factors in each one of these five on the left side there.

Well when you’re planning something you know a land developer wants to go out and build the big massive subdivision say he wants to know what’s the rough area that I’ve got to build on. How many homes can I roughly get on there? And he just trying to get an idea. Is it worth it for me or not to make some money on this and then you get into the designing phase you’ve gone out and figured out what the lay of the land is in and said here is the boundary of the area that you purchased to do all of this, so they get down to nittier gritty, they start designing roads and an actual lot for these buildings. And then you get in the construction phase when you go out you can stake out these roads that some engineer designs for him and here’s where the building needs to be a house on each one of these lots and the driveways and all the utilities. The as-built phase after everything is constructed it’s good to go out. Here’s how we designed it how close they get to the design? And if we need to go back later with what got put into the ground and then in the demolition phase you want to rework something. A homeowner doesn’t like his house, or it gets blown over or whatever and they need to demo and then come back in and build something new. And that one can even go back into the planning phase. There is an old barn out there that need to get rid of and get it located in the planning phase.

And survey will be involved in pretty much each one of these.

Every single one.

I know we briefly mentioned this earlier but you know when you’re talking about you know why is land surveying so important. You know there’s many different reasons, we’ve listed a few of them here on the left, but tell us why land surveying is needed. Let’s say you’re going to build a building. You’re in your planning or your design and you just decide you want to save a few dollars, let’s not do land surveying. What are the potential repercussions?

Potential repercussions you might not build on the land that you thought was yours because you didn’t have somebody go out there and figure out where your land is.

What happens if you end up building on land that’s not yours and you go over a boundary that now is somebody else’s?

You get an angry landowner and an angry adjacent land owner and he’s going to take you to court and make you either tear it down or he’s going to say well it’s on my land, that portion of that is mine. Both of those options sound expensive when you compare it to just using a land surveyor on the front end to gather this. Yeah when you spend millions of dollars on a single building. You want to make sure that it’s all on your property. Unless you make an agreement with the guy next door.

You want to know exactly what your terrain looks like so that you don’t have maybe you don’t want to bring in a whole lot of dirt to grade on this thing to try to balance if you don’t have a surveyor go out there and get the topography for you. You’re not going to be able to grade it accurately.

Kind of the first bullet point there, understanding what is there. I mean there if there’s too much grading that occurs, there’s too much construction cut and fill, that could get very expensive. And maybe that’s not the ideal place to put that new mall or to put that new building or movie theater. Right? So, understanding what is there and then understanding how to build it. Obviously, you know tell us a little bit about that. How does that factor in, putting in these stakes that we see when we drive by these open lots?

Yeah, I mean the engineering that goes into the construction plans for any project there’s a lot that goes into it and if you don’t put it into the ground correctly you know all the expensive work that went into that it was for nothing. You know, and we want to make sure that water flows downhill the place that it’s supposed to go. If you don’t have a surveyor come in and stake it out for you it may, who knows where it will go. And then things start flooding and the person that bought that property then they’re not happy because they’re probably just flooded.

I think most of the folks who might be listening, they can understand, especially if they work with surveying in the past, this is a needed thing. Right. I mean people they shouldn’t or wouldn’t not use surveying on the front end of this and all the way through the process because it is extremely costly, and the project timeline could just get completely thrown out. If don’t understand what you’re doing. That accuracy of the information and knowing where you’re going to fill. Why are you going to build it that way? How are you going to build that? All those factors that come in. Right. The survey is an important piece of that. All the way through. And if you don’t have that or it’s not done accurately that could be another problem.

Accuracy is huge. You know like I was saying if you don’t put it in writing and water is going to flow over it is not supposed to go or you might put that fence line in the wrong spot. Accuracy is important.

Well let’s switch gears a little bit here let’s talk about types of land surveying. I know there’s a lot of different types of land surveying but some of the more common terms that you’ll hear like topographic type surveys or boundaries surveys or boundary surveys or construction surveys, or there’s a lot of different ones. We live just kind of under the more common ones here. OK I’d love to kind of ease a little bit more and maybe you can help educate our listeners and myself on what each one of these means. Why are they important? So, let’s start with topographic surveys. So, what it this, why is it used, how does it benefit the overall process?

Well, topographic survey tells you what does the land look like? What’s on the land? Buildings, fences, roads and what kind of vertical relief is there on the ground. You can see there on the left you’ve got contours which gives you lines of constant elevation and you can get a good idea three dimensionally what that land looks like and where the lakes are. And then on the right you’ve got one that was done for a grading plan for an oil and gas pad.

Okay so these topographic surveys, these contours that you mentioned again for in layman’s terms you’re talking about contour I can see all these squiggly lines there. What do those mean? I know you have mentioned that shows the elevations but if they’re closer together what does that mean? We’ve seen some of these maps before. What happens if they’re further away? So just describe what that means.

The closer together they are the steeper the land the farther apart they are the flatter the land.

And so generally if somebody’s building something just from a planning phase they may want to look at like one-foot contours. You know you hear those terms. What does that mean?

One-foot contours is the interval between contours on the map itself.

They want you to measure within 1’, or to be able to measure within one foot?

They want within a foot to know what the topography looks like. There’s something that is flat. You might even give them half a foot contours or even down to a tenth. Just to give them a better idea of what’s happening in between these one-foot contours, if it’s flat you’re not going to see a lot of relief within that area.

And then the things you mentioned roads, houses, things like that, are those what you would commonly refer to as features or other terms for that?

I would generally call those features that’s what I like to call them.

And the topographic ultimately not only will tell you or show you the lakes or any types of drainage or things like that that might be around there but also does that ultimately help you figure out what that cut and fill we talked about earlier like how much you’re going to need to cut and fill and when you start grading out that area to make it flat.

You’ll use it for calculations to figure out how much cut and fill you’re going to have and you can even use those contours to give you an idea of where streams are to a trained eye. And you can see where the contours kind of make a point. And that’s sometimes a valley or a ridge.

Another very common term that we that we hear is section breakdown. Explain what section break down is. What are you doing? Why is that important?

Well you know we talked about PLSS and everything is broken down into sections and a lot of times land here in Colorado is described in terms of sections at least the rural areas the urbanized have been subdivided even further. You need to go out and you need to locate the corners of these 1-mile sections and then sometimes even farther down than that the quarter-quarter. The surveyors back and 1800s, they laid stones out, or charred stakes, or piles of rocks. They used all sorts of different methods, but they generally set them at the section corners or the quarter corners on the exteriors.

Why are you going out there and verifying that these monuments are there? That’s a section break down right ultimately going out and saying these monuments are here. Why do you need to verify that they’re there? They were put in there 200 years ago why do we need to go back out and verify that those are there?

They were put in two hundred years ago and we didn’t have any way to say here’s exactly where it is. I mean they were accurate, but they weren’t that accurate, so nothing was exactly a mile and a lot of our clients are oil and gas and they have to know within foot where their oil well is relative to a section line.

Well let me give you another example. Let’s say it wasn’t two hundred years ago what if it was five years ago? Why would you still need to go out and verify that there is a monument on this corner of these four sections?

Well things like road construction happen. They repave a road, or they pave a dirt road, a cow gets hungry, sometimes a landowner and some of these old limestone sandstones that they put out 150 years ago, they’re pretty and Ma Farmer wants to have around her garden and sometimes they just get pulled out. Things like that. They are obliterated, and we must go back out and re-establish those corners.

And how often do you have to go out and re-establish or verify that the monuments are there?

Well the verification, we do it all the time. Re-establishing one anywhere roughly around 25 percent of the time we must reestablish the monument has been lost or obliterated.

Really 25? Let’s stop there just for a second. What if you go out to verify that there was a monument there and it’s not there. What is the obligation from your perspective as a PLS, you’re a professional land surveyor, or as a company? What’s your obligation if you go out there to verify that something’s there and it’s not there?

Well we have an obligation as a surveyor by Colorado State statute to re-establish that monument and the location of that. And we used various methods. There’s lines of occupation if there’s a fence line, it makes it obvious where that corner is if there’s a fence corner. We must consider road right of ways and things like that. There are other surveying methods, proportional methods that we can use to establish that corner again.

I would imagine that that can make a tough situation because the project itself that you may be working on may not necessitate that you’re going out and reestablishing an entire monument. But the Colorado statutes say yes you should be doing that. So is it fair to say that there could be a bit of a conflict there because you know the company you might be working for they couldn’t care less they just want an accurate survey. But your license potentially could be on the line if you’re not if you’re not doing that right.

Correct.

Yeah. State law.

I imagine just to go re-establish a monument, as easy as that may sound it’s not as easy as it sounds.

No. There’s a lot more research that goes into it. You must expand your surveying to get additional monumentation or additional lines of occupation.

And that costs money. You’ve got to maybe you title research, expand the survey. This is all going to be more hours that go into that project that the client may say, “I don’t want that. I didn’t pay for you to go do title research.” But unfortunately, that’s something that you must do. This is an important one, we’ve been talking about Section Break down for a few minutes, but this can be an area of contention in some situations because this is a tough deal. Section break down is anything but easy and anything but a known certainty of what you’re going to find out there. As we know, finding monuments can be a tricky task. You can see some of the images here. Just looking at where you’re going to have to try and find monuments. Tell me a little bit about this. What types of variation you can find. You could find one maybe six inches under the ground and you could find one that’s six feet.

You bet. The original monument might have been set, you can see the one there in the upper left corner. Owen’s short, but he’s not that short. But the road’s been built, and they paved over the top of it. And that monument was probably five feet under the ground. And then you know we live in Colorado it snows sometimes you have to go out and dig for it. The one in the upper right shows pretty close but it was in pavement and it was buried underneath that pavement, so you’ve got to go, and you got to chip away at that asphalt it’s not easy to get to all of the time. Right below again same deal and then there are some areas you get up into northern Weld county where there’s some wicked terrain that one in the middle and you know it’s not easy to get around in areas like that. But the surveyors hundreds of years ago they placed them where they were supposed to be. If there was no water. They put it where it’s supposed to be, so it’s probably down in that ravine somewhere and sometimes it is on a rock cliff.

That’s scary stuff, and it’s funny because the one that is up there in the middle with the snow there I’m going to take a wild guess that the ground underneath the four feet of snow is probably not the softest stuff in the world right.

Generally, not.

I imagine that ground is hard. What are you using to pull up these monuments, obviously you can see that you’re digging there? What are you using to dig up these monuments?

Whatever we can. A shovel, a pick axe, chisels. If we could, we’d probably take a blowtorch out there and defrost the ground, but we generally can’t carry one of those with us.

Anything you can break up that and I know that in some cases it’s as hard as concrete.

And it’s delicate when you get close to it, so you don’t want to disturb that monument or destroy the top of it. In some ways it’s like being an archaeologist. You dig until you get close and then you know we don’t go as far as getting out the brush to get the bone out or anything.

Well you can see up in the top right there is the monument, we call those caps as more of a modern technique obviously, but you’ve also got old monuments out there, too right? I mean you got in some of these areas up in North Weld County on the Colorado Wyoming border area and some of those areas. I imagine if you’re in Wyoming or just some of those areas you’re going to find old monuments.

Yes, a lot of those monuments that they set a hundred and fifty years ago were stones and you can see on some of these. They’ve got little notches on them and told them how far away they were from the east or south edge of the township depending on where a lot of notches were on the face of the stone and other ones were putting a large stick in the ground maybe they ran out of stones, so they put in a branch and then other ones were charred stakes or piles of rocks there and the stone mounds in the bottom right. But that’s a lot of the ways. It used to look like that around Denver, but we’ve had development and everything. So now a lot of it is aluminum caps, brass caps.

There’s a lot that goes in that section break down. Last question for you on that and then we’ll move to the next one is if I asked you to go out into a township and I just picked two sections and I said I need you to go break down these two sections in this township, and I said I need you to give me an exact cost for what that’s going to be. Would you be able to do it?

I could not.

Why?

I don’t know what section monuments are still there and what doesn’t exist. Unfortunately, without going out there I can’t know exactly how long it’s going to take. If all the monuments are there, it will go pretty fast. But if some of them are gone and I need to establish them via other methods, there is no telling how long the extra cost could be.

You have no idea what’s out there, what you may have to verify, how you would have to verify, you may have to dig six feet, are you going to have to re-establish a monument, are you potentially going to be looking for rocks that notches in them, are you. is the weather going to play into it – where you might be digging for two hours on something that might take 15 minutes in the summer? A lot of factors, a lot of variables. outside so that construction stage.

Let’s talk about construction staking. Once you’ve got some section break down and you’ve established where those monuments are, and no, why you’re going to use those monuments is so that you can kind of triangulate off that to understand the area.

Section monuments helps subdividing back into either smaller pieces or a lot of subdivisions around here are done in some portion of a section or an entire section. But then you get into a house lot and it’s not a perfect square or a rectangle. Curved roads. Cul-de-sacs.

Then ultimately once you figure that out you’re going to have to do this service called construction staking. What is construction staking? Why is it used, and how does that help the project? What function is it serving on the project?

Construction staking makes sure that everything gets built where it’s supposed to be built. Doesn’t always happen. Some contractors don’t understand what you were staking, or things get bumped and they don’t ask a surveyor to come out and re-stake it for them.

What do you mean bumped?

Well I have personally gone out and staked something for the land developer on one day and then somebody comes through that afternoon with a grader and then the guy that was going to place that storm drain in the ground can’t find the stakes that I put in because the grader came by and took out my stakes. The guy putting in the storm drain says, “Well, I’ve still got this stake and that stake, I’m just going to put it in between those.” And then it turns out to not be right. Construction staking makes sure that things get put in the ground and built as close to the plans as possible.

I mean over the years as a kid I never knew what those things were I’m sure I pulled a few of them out and played sword fighting with them on occasion but these wood stakes here this is what we’re talking about when we say staking, are these wood stakes or lath. What are the flags that are on there, you see these colors of ribbons that are on there?

It’s a way to draw attention to it. It is a survey position sometimes some surveyors or some contractors will want certain colors to mean certain things. For instance, I’ve used blue as a water stake, green is a sewer stake, white is a storm drain, but different contractors, different surveyors use different colors here it’s orange and this looks like a curb stake to me. And it’s a three-foot offset that’s up there at the top of that and BC is for back curb. And then from the nail or whatever is fill of 0.68 feet from the back of curb. So now all that information is there for the contractor, and he knows to take three feet away and go up two thirds of a foot and then that’s where his back curb is.

Survey is coming in and that’s why again that accuracy is extremely important because they’re putting something in the ground exactly where this is where it needs to go. This is how much dirt they may have to move for a separate construction company to come in, or an earth removal company or whatever that’s going to be coming in after that. You’ve got two completely different entities, companies working together a lot of detail and accuracy has been put in place here for this to be built correctly.

Yeah, the accuracy part. Here on the eastern plains it’s kind of flat, and we don’t put a lot of slope on our roads. Sometimes it is as little as a half a percent and a half percent is not much. That might be a foot over a hundred feet. We put our stakes 25 feet apart. If you don’t have the right elevations on there, or it’s not built correctly, the water isn’t going to flow right. When you’ve got half a percent, water must flow in right direction.

Let’s move on to as-builts. We talked about topographic survey kind of on the front end getting planning pieces of those, we talked about going through and doing a section break down piece to make sure that you’re tying everything to the monuments, you know exactly where it’s at, and then the construction staking. That leads us to this as-built. What does as-built mean and why is it used for a project?

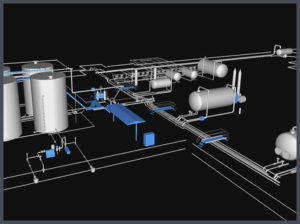

As-built is: how was it constructed? Plans are put together on how to build something, but nothing ever goes as planned. Very seldom does a project go as planned so you always want to do an as-built survey after it’s done. How was it built? And that’s important especially for something like an upstream facility that you see here. Things change. Technology changes. They want to expand the site – this is an oil and gas site of some sort. And they might want to expand it. So how is it built? Where, when I go to design something that I’m going to expand this on, where can I connect to get to?

As-built, if you listen to it as it’s stated, it seems to me that you’re surveying the actual building as it’s being built. But you’re saying that this happens a lot of times it’s on the back end it.

Oh yeah absolutely. For residential subdivisions the whole street will be done, and you will come in afterwards and determine how it was built. How is that water going to flow in the curb and gutter, we will dip the manholes, and make sure that the inverts are correct on a sewer line. You would think that, especially the sewer line, why don’t I do it right after they put it in the ground? Sometimes the sewer lines here in Colorado are 15 feet deep because we have basements. I could take a shot on it before they fill it, but when you put 15 feet of dirt on it, things tend to settle a little bit, so where I took the shot before they put dirt on it compared to after the dirt is put on can be significantly different at times.

When you say, “Take a shot,” you’re talking about what?

Going out with my instrument and getting that location horizontally and vertically.

A GPS coordinates?

Whether with GPS or traditional survey methods using a total station.

How often does it happen where what you built you go in and do the as-built, and it actually matches the original perfectly?

Well, exactly? I’m going to say next to never because construction methods are not perfect, surveying methods are not perfect. We have tolerances in the survey community so it’s almost never. Even an as-built survey is not going to be exact but it’s going to be better than the plans. At least you have a good idea of where it is after. I would say I don’t even want to put a percentage to it.

You’d think, on the front end, if using it for planning, using it for design, and using it, you know, all the way through, that when you do the as-built, it should certainly match but obviously we see that doesn’t happen a lot.

Right. It can be close, and it could be way off. It could have been conditions in the field that they had to field fit something, and it’s completely different than what the plan was. And it never went through a redesign phase. The contractor said I don’t have time to wait for them to redesign this thing; I’m going to wrap this pipe this way.

You’re really hoping at the end an opinion that that will work rather than not, if the as-built is quite a bit off. That could be timely and expensive. So, we’ve talked a lot about the history of where it came from, and talked about the different types of surveying. Let’s take a quick second to talk about the future of land surveying. So, you’ve been in surveying for 90 plus years. But you’ve also been on the on the cutting edge of a lot of the new types of technology that’s being used so where do you see the future of land surveying going?

Well, first, it’s been more around 25 years, maybe 30. I can’t remember back that far. I learned on some traditional equipment, transits, and I grew up through the age of total stations, and then robotic total stations now and then we got GPS which makes it cool, we can go out and get our information from the satellites and locate something. Levels help us certainly in areas where things are flat, and we need to make sure that the elevations are tight. 3-D laser scanning it’s been around for 10, 15, 20 years, but it’s really made some strides in the last five years. The technology and how fast and accurately it can gather that data. Some of the original scanners were about fifty points per second and now we’re up to a million points per second. And then UAVs, unmanned aerial vehicles or drones, it’s been two or three years that those have been making strides in surveying. We used to send up a Cessna plane or something like that and get aerial images and get our surveying that way. Now we’re doing that with these tiny helicopters or these fixed wing aircraft that we just send up in a small area and it comes back down and we do our own aerial imagery now.

Compared to a conventional aircraft, where you can just send it up in an hour – as opposed to having to plan that out for weeks, and there’s a big cost difference there. You’re flying 350 to 400 feet above the ground compared to 2,000 feet potentially. I would imagine you can get some good accuracy that you might not be able to get otherwise. The 3D laser scanning, we’re talking about LiDAR, or light detection and ranging, which is similar to sonar and similar to radar, where it’s sending out pulse and getting a return. Only in this case we’re talking about sending out millions of different pulses and creating this 3-D visual data. This new technology is moving from this 2-D environment into a 3-D environment where now you get these 3-D surface models and 3-D point clouds that you can do all kinds of things with.

I call 3D laser scanning or HDS, like I call it GPS on steroids. Where we used to go out and get a shot at the bottom of the tree, and then we used our comments and our field book, and say, “Okay, this is a 12 inch tree and maybe get a couple shots on the drip line. 3D laser scanning gets the entire tree.

It gets it all, every single bit, every millimeter out there and that’s kind of the big idea. Now what these tools are able to do is get more information. When you’re talking about conventional versus using UAV or drones (use those terms synonymously, they’re the same thing), and LIDAR, we’re talking about gathering a tremendous amount of data more than what you’d be able to get conventionally.

In conventional surveying, there is a typical grid survey going out getting the topography of an open field or something. Depending on the visual relief on there, we might do a 50-foot grid or 25 or even sometimes 100-foot grid and even there, inside there is little undulations that you can’t get, you’d be out there all day trying to do that by hand, and with LIDAR, it gathers the data so fast that you get what you see there and the relief at the bottom right. What you didn’t get on a 50-foot grid, you see a lot more in that on the LiDAR or the UAV.

You take out the guessing game of what’s out there. You know it isn’t straight lines, we all know it’s not just straight lines out there. There are going to be those undulations. Knowing exactly what’s there is beneficial. It doesn’t take any more time, in fact it probably takes less field time to gather that amount of information now than a surveyor walking around with a GPS. Ultimately, we talk about collecting more data using UAV as an example, but it’s also about collecting more area. In this example, that’s about one thousand acres there that we, as a company, collected in about three hours with UAVs. This is providing two different benefits here one is on the left is an orthomosaic, which could be hundreds of thousands of pictures that are stitched together, which leads to the most up to date aerial imagery that is out there. This is a big advantage, because now it’s not a guessing game; we’re not using Google Earth that could be three months or three years old. Orthomosaics allow you to know exactly what’s out there. Here in Colorado, we have a lot of development going on, a lot of new housing communities going in. The difference of looking at Google Earth, which could be two years old, and knowing that there is an actual housing community going in there, could be important. Or Texas, where there’s a lot of oil and gas new locations going in every single day, new pipelines being put in place every day. To be able to see a pipeline scar, or an above ground gathering is very important. Having that up-to-date aerial imagery would be important, especially if you’re an engineer or you’re a surveyor.

From where I started out, we’d send up a big plane and that was expensive, so most of the time we didn’t even do aerial imagery. We relied on what we could get by shooting points on the ground. Then the Internet came along, and Google Earth came along, and we thought, “Wow, now we can see what it looks like from the ground, we can get some background to our drawings.” But that’s two or three years old, and I have had many instances where I used Google Earth, and when we go out there, it’s completely different because development happens and it’s just not the same anymore. Being able to send up a small drone and get these images in a short amount of time has been a huge help.

It’s not just the aerial imagery, we’re also gathering data out there. It’s not just flying and getting nice, pretty pictures of what’s out there. We’re also getting data, as you can see on the right side there, we’re looking at the topography that we got earlier and getting those contours. Now we know what the Earth is doing on a thousand acres. No one is going to pay a surveyor to go collect one thousand acres of data unless they’re going to build on one thousand acres. Now, if they’re using 100 acres, they will just have you survey the 100 acres. But then, plans change, and surveyors go back out. We get called back out to the same location five, six, seven times to survey the same exact location because plans change. You know that oil and gas pad moves 200 feet to the right. Now we must go survey and find out what that topography looks like. Being able to gather all of this on the front end and getting these features that are there, the cultural information that is out there, and establishing the setbacks, etc. Now when things change, we can pull it up on a computer, instead of sending a survey crew back out, which extends the timeline, and adds additional cost to the project, we can just pull up this data on our computers and decide where we want to go. We can then decide, “We can’t go 200 feet to the east because it is too steep of a grade, we can’t go to the north because there’s a building unit. Maybe we’ll go 300 feet to the south or 400 feet to the west. And those are our options. Where do you want to go with it?”

I like to call that collateral data. You know we’ve all heard of collateral damage. You wanted to blow up this building and something over there got hit, too, or you didn’t intend for that, but it happened. That’s the great thing about aerial surveying and HDS laser scanning is you get a lot of collateral data is what I like to call it. You didn’t intend to get that they didn’t need that data at the time, but plans change and because of the methods used to gather that data you already have it.

That makes a huge difference on the efficiencies of these different projects. This is a 3D point cloud. It looks like a drone is just flying around taking this nice video, and it’s not. This is a 3-D point cloud. This is all data that we’re looking at. This is the data that we can measure based off geospatial points. We’re also able to get that visual depth 3D visualization, which is extremely helpful for several different purposes. We’ve figured out 10 or 15 different purposes for using this type of data. It’s powerful to be able to get this amount of area and then pick – why we call it a fly-through is because we’re choosing to fly through this big point cloud at this particular angle, but you could go at any angle, we could go directly above it, look at it from the side look at it going around in circle, lots of different ways. When you started your career surveying, did you have anything like this that you could use? If not, where would it have provided benefits?

I can only do this with my dad’s plane. We would go up and take pictures. Nothing like this when I first started surveying. The technology and the fact that this is not just the actual footage from the drone, this is the fly-through of the data that was captured, it’s amazing where technology has gone.

You’re looking at a thousand acres in a visual example here that could potentially be spot on. Now maybe it’s off 1/10th horizontally and maybe 2/10ths vertically; that’s amazing on this amount of area. A lot of decisions can be made when you have that actual data at your fingertips.

Yeah, and that accuracy, when we saw the 50-foot grid a couple of slides ago, in those days, we figured any contour that was drawn from that was within about six inches. you know. And now we say that the data is accurate with a couple of tenths, that’s even more accurate than what we had before, even though the point that we shot on that 50-foot grid was a little more accurate. We didn’t have any data in between there. Now we’ve got data in-between those to a greater accuracy than we could claim our old-style methods of surveying.

It’s been a huge change you know moving to this 3D environment, and there’re good marketing purposes it can be used for, if you know think about going into a new project and you take something like what’s on the ground and overlay your design plans on top of that. Tell someone that this is what it’s going to look like to give somebody a 3D visual on a video like this. Or pre-construction, post-construction, progress reporting and show the evolution of that project, and this is what it’s looked like as it’s gone through. A lot of people like to see these. New communities are being built. There’s a new shopping center going in or a new oil and gas pad. People want to see what this is going to look like from my house or my back porch. Having that visual is also helpful from a marketing perspective.

We can take that design and put it on top of that fly-through to give people a nice plan of what’s it going to look like.

So that is that is a quick Land Surveying 101. Now we’ll be taking questions and in that top right-hand corner if you click that orange arrow, you can leave a question. The first question that we’ve got here is calculation of points. Explain what that means.

A lot of times especially for construction staking an engineer designs something and then the surveyor is going to take his engineering plans and we’re going to calculate points so that we can go out and perform that construction staking. We can also calculate points when we’re doing section breakdown. If we’ve got some of the corners, but we can’t find another one maybe we’ll calculate where we think it should be, and sometimes we were just searching in the wrong area based on other monumentation around, and then when we get a more accurate calculation on that, we find the original monument.

Is there a danger to calculating points if you’re doing section breakdown, as an example?

No, there’s never a danger in calculating points, unless you’re calculating it wrong.

What if you’re calculating off something that you haven’t verified is there.

Then, there is a danger.

There probably are some firms that are out there – survey firms – that maybe surveyed an area 20 years ago and did find a monument 20 years ago that have not gone back out to re-verify that that is there and maybe possibly calculating points off a monument that maybe doesn’t exist there anymore. There is a danger in that, then?

Absolutely. Things could have happened in the last 20 years, maybe that first monument wasn’t in the location where it should have been. Other things have come to light that the actual monument was 50 feet to the west because somebody didn’t take into account a roadway that was dedicated 50 years ago.

Is it safe to say that surveyors are following in the footsteps of previous surveyors and verifying that what should be there is there?

Yeah, as surveyors we do a lot of following. We follow all of the surveys that have gone before us and we hope that those surveyors before us left us a good bread trail. Sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t. If they do, it makes our investigation a lot easier, and if they don’t then we just start the investigation all over again to reestablish what should be there.

Let’s move on to the next question. Why would you not or why would you want to use two different land surveyors on the job? We’ve had these in the past. What are the pros and cons?

The pros if there’s contention as to the location of a boundary line no, two surveyors are going to come up to the same solution. A lot of surveying is based on opinion, professional opinion, and sometimes we’ll come up with the same solution but a lot of times we don’t. We might be a little bit different. Someone might find a piece of recorded evidence and another surveyor may find something that wasn’t recorded. If there is a land contention, then there is possibly an advantage to having a second opinion just like with a doctor. The cons to having a second surveyor or a second opinion on the surveying depending on the reason it’s just an added cost that you don’t really need.

What it would if you had a surveyor on the front end doing the topographic survey and the planning but a different one on the back end doing construction staking or the as-built survey?

Your con there is that you’re adding another surveyor that is not familiar with the project. If they’re a good reputable surveyor, they’re going to go out and establish either their own control network or verifying your control network. They’re just doubling up on the work that you originally did. So that’s an added cost that you don’t really need that the developers shouldn’t have to bear.

If you’ve got two folks working on it and something goes wrong, who’s to blame? Where do you point the finger there? With multiple surveyors, one’s going to point their finger at the other one. Another question: How are survey inches and feet different to regular inches and feet?

Surveyors don’t use inches. There is an international foot, and a US survey foot. They don’t differ by a lot, on a ruler, it’s pretty much the same, but they do differ when you get on a long distance. I can’t remember the exact difference off the top of my head but here in the U.S. obviously we use a U.S. survey foot. There are some states, I believe Montana is one of them, that uses an international foot.

We know a regular foot to be twelve inches, but how big would a survey foot be?

It is still roughly 12 inches. I mean there’s a fraction of a difference. On a ruler, you won’t be able to tell the difference. But when you get out on a long distance, if you’re in international or you’re in survey foot, you’ll see a difference. Generally, a surveyor does not work in inches. When we break it down below a foot, we’ll go down to the tenths of a foot and then to the hundredths.

And when you say tenth, you’re talking about those 10 survey inches for lack of a better way of putting that in a regular 12-inch foot?

Yeah, the foot is divided in 10 segments instead of 12. Then, we’ll break that down into tenths for a hundredth. So that a foot is broken down into a hundred different pieces.

Last question here. Why is it that you could find six different monuments at the same exact location?

No two surveyors have the same opinion of where something is. When you get into that, what we call pin-cushioning, usually you have surveyors who think their position is a little more accurate than yours. Where generally the edge is the accuracy, the equipment, the way that surveyor interpreted it. One surveyor feels his monument is one foot different than the marked on, and instead of putting in his notes that he feels it’s a foot different, he places a new monument.

Say there’re two different monuments, and let’s say there’s an error that something has been built wrong, two different surveyors have been involved in the project, one surveyed this area, one surveyed that area, they found the same section corner. Is it fair to say that they could both be correct, and they could both be wrong?

Yes.

That’s really confusing.

Yes. You have two surveyors with two different monuments. You could bring in two more surveyors and they could say that one of them is right. One says one’s right. One says the other one is right. So like I said, it’s all up to professional opinion and then it’s up to the lawyer to decide who actually is right.

Clear as mud. As long as you have evidence and can show what you did to prove why that was the monument that you chose and why that was the spot that you picked, then that’s really what it’s about. Tracing your steps and showing your math.

Leaving those bread crumbs. Not only for surveyors coming behind you, but for yourself, so that you know how you did it, and if you must explain to someone, you can show them on paper how you came to that conclusion.

Well, thank you for your expertise, Michael. This concludes our webinar.

Bio coming soon.

Bio coming soon. Hold for Lisa McCool bio.

Hold for Lisa McCool bio. Hold for Christie Petersen bio.

Hold for Christie Petersen bio. Scott Bass manages all Colorado survey crews at Ascent. He began at Ascent in 2019, and has a variety of skills, including GPS and Conventional field survey locations, AutoCAD Drafting, Revit drafting, Bid Package Preparations, Directing Operations, Business Development, Project Budgeting, and Deed Research/Analysis.

Scott Bass manages all Colorado survey crews at Ascent. He began at Ascent in 2019, and has a variety of skills, including GPS and Conventional field survey locations, AutoCAD Drafting, Revit drafting, Bid Package Preparations, Directing Operations, Business Development, Project Budgeting, and Deed Research/Analysis. Hold for Matt Morris bio.

Hold for Matt Morris bio.

Chief People Officer

Chief People Officer Ramsey joined the Ascent team in November of 2017 and is CFO, as well as overseeing the Accounting, Finance, IT and Operations functions of Ascent. Ramsey brings more than a decade of finance experience across multiple disciplines including budgeting, FP&A, M&A, controllership, pricing and contract negotiations and treasury management.

Ramsey joined the Ascent team in November of 2017 and is CFO, as well as overseeing the Accounting, Finance, IT and Operations functions of Ascent. Ramsey brings more than a decade of finance experience across multiple disciplines including budgeting, FP&A, M&A, controllership, pricing and contract negotiations and treasury management. Founder

Founder Chief Executive Officer

Chief Executive Officer Regulatory Manager

Regulatory Manager Director of Innovation

Director of Innovation Chief Operating Officer

Chief Operating Officer Jerry has more than 30 years of technical and project management experience in the field of land surveying. As a retired Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) employee of 30 years, he brings his knowledge of CDOT procedure and techniques to the team. He is involved in the day to day process, procedures, and workflows of the infrastructure related projects, project phase and tasks, and verifying the delivery of survey data for the infrastructure projects. Primary functions include the QA/QC of daily and final survey deliverables, project management, researching Right of Way records, ensuring Federal, State, County, and Local requirements are met, and the signing and sealing of survey related documents for recording. Jerry has been a licensed Professional Land Surveyor in Colorado since 1994.

Jerry has more than 30 years of technical and project management experience in the field of land surveying. As a retired Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) employee of 30 years, he brings his knowledge of CDOT procedure and techniques to the team. He is involved in the day to day process, procedures, and workflows of the infrastructure related projects, project phase and tasks, and verifying the delivery of survey data for the infrastructure projects. Primary functions include the QA/QC of daily and final survey deliverables, project management, researching Right of Way records, ensuring Federal, State, County, and Local requirements are met, and the signing and sealing of survey related documents for recording. Jerry has been a licensed Professional Land Surveyor in Colorado since 1994. Program Manager

Program Manager

Bob has more than 40 years of experience in the surveying and mapping professions. He has worked in the capacity of owner, survey manager, office manager, and project manager for surveying, construction and engineering firms. As a Professional Land Surveyor, he has experience working on survey projects involving Primary control layout, construction, boundary, mining, oil-gas, topographic, and design. He has provided these services to a variety of clients including CDOT, Arapahoe County, Jefferson County, Clear Creek County, City and County of Denver, private engineering firms including CH2M Hill, Carter Burgess, J.F. Sato, Merrick & Co, Washington Group, Nolte Associate, and construction companies including Johnson Brothers Construction, Ames Construction Co., Sema Construction Co., KiewitWestern Construction, Kelly Construction and Lawrence Construction Co. Bob has been a Licensed Professional Land Surveyor since 1983, and holds an Associate Degree in Surveying from Red Rocks Community College.

Bob has more than 40 years of experience in the surveying and mapping professions. He has worked in the capacity of owner, survey manager, office manager, and project manager for surveying, construction and engineering firms. As a Professional Land Surveyor, he has experience working on survey projects involving Primary control layout, construction, boundary, mining, oil-gas, topographic, and design. He has provided these services to a variety of clients including CDOT, Arapahoe County, Jefferson County, Clear Creek County, City and County of Denver, private engineering firms including CH2M Hill, Carter Burgess, J.F. Sato, Merrick & Co, Washington Group, Nolte Associate, and construction companies including Johnson Brothers Construction, Ames Construction Co., Sema Construction Co., KiewitWestern Construction, Kelly Construction and Lawrence Construction Co. Bob has been a Licensed Professional Land Surveyor since 1983, and holds an Associate Degree in Surveying from Red Rocks Community College. Productions Manager

Productions Manager Engineering Manager

Engineering Manager GIS Manager

GIS Manager Senior Field Coordinator/Crew Chief

Senior Field Coordinator/Crew Chief Colorado

Colorado Data Processing Specialist

Data Processing Specialist Controller

Controller

Upstream oil & gas operators have one simple goal: find and drill hydrocarbons. To do this, operators must navigate the regulatory gauntlet to receive their necessary permits. Without the proper expertise and experience, operators can lose valuable time and possibly even lose the location itself to another operator.

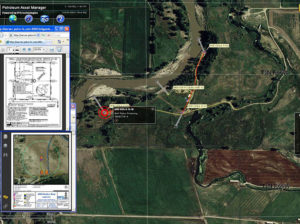

Upstream oil & gas operators have one simple goal: find and drill hydrocarbons. To do this, operators must navigate the regulatory gauntlet to receive their necessary permits. Without the proper expertise and experience, operators can lose valuable time and possibly even lose the location itself to another operator. Extended Text for Popup: The ability to manage all your assets is critical to running an efficient organization. Having the ability to view floodplain, wildlife and/or utility lines can help operators better plan their sites for Surface Use Agreements (SUA).

Extended Text for Popup: The ability to manage all your assets is critical to running an efficient organization. Having the ability to view floodplain, wildlife and/or utility lines can help operators better plan their sites for Surface Use Agreements (SUA). Viewing up-to-date aerial imagery can help save companies thousands of dollars by avoiding previously unforeseen challenges at the site location.

Viewing up-to-date aerial imagery can help save companies thousands of dollars by avoiding previously unforeseen challenges at the site location. Most oil & gas operators will create as-built drawings for their well pads, pipelines, facilities and any other construction related projects. ASCENT has completed thousands of as-built surveys and drawings for our clients. Our extensive experience has taught us the most efficient and cost effective ways to create these as-built deliverables.

Most oil & gas operators will create as-built drawings for their well pads, pipelines, facilities and any other construction related projects. ASCENT has completed thousands of as-built surveys and drawings for our clients. Our extensive experience has taught us the most efficient and cost effective ways to create these as-built deliverables. When companies are looking to design, or modify a facility, there is no reason not to use LiDAR technology. LiDAR provides design-grade accuracy with 3D modeling to see how the facility will look after construction.

When companies are looking to design, or modify a facility, there is no reason not to use LiDAR technology. LiDAR provides design-grade accuracy with 3D modeling to see how the facility will look after construction. Pipeline projects can cost millions of dollars. Missing the project timelines can cost midstream operators even more money. That is why planning on the front-end of the project is so important.

Pipeline projects can cost millions of dollars. Missing the project timelines can cost midstream operators even more money. That is why planning on the front-end of the project is so important. Longer pipeline corridors can take a significant amount of time to create topographic surveys with traditional methods. With aerial LiDAR, ASCENT can significantly reduce the time it takes to create these topographic surveys while providing a tremendous amount of useful data. This highly accurate pre-construction LiDAR data can then be married with highly accurate after-built LiDAR data to determine the precision of the planned and constructed pipeline.

Longer pipeline corridors can take a significant amount of time to create topographic surveys with traditional methods. With aerial LiDAR, ASCENT can significantly reduce the time it takes to create these topographic surveys while providing a tremendous amount of useful data. This highly accurate pre-construction LiDAR data can then be married with highly accurate after-built LiDAR data to determine the precision of the planned and constructed pipeline.